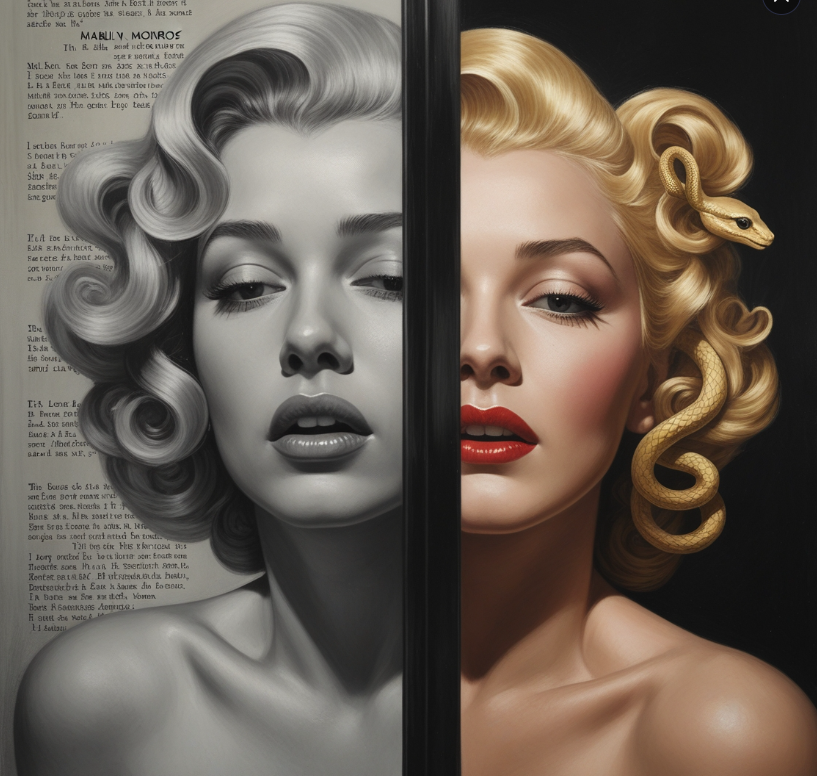

American Mythos: Medusa & Monroe – Aya Almohtadi

The West in the meantime was not dealing its cards in favor of women either, it has rather gone far enough to create its own enduring Greek Myth of the time: Marilyn Monroe. Marilyn did not come out of the woodwork, her name was Norma Jean Baker—the face of Eve that the media strived so hard to hide—, born to an unknown father and to an unstable mother who was institutionalized shortly after Marilyn’s birth, leaving her daughter to cycle through orphanages and foster homes till she was married off at 16 to police officer James Dougherty in 1942. They divorce 4 years later as she attempts to pursue an acting career, save that Norma was neither androgynous nor brutish in her aspiring for a career, she rose to fame to become America’s 20th century sex symbol.

One might view her career as a going against the grain, as she managed to become a successful woman when all the odds were stacked up against aspiring women her age. Another might argue that Marilyn was perpetuating the objectification of women which lies at the origin of their inability to advance beyond being seen as mothers, wives or sexual objects. While Marilyn might have done so, Norma was striving restlessly to break out of the vicious cycle, only this time her opponent was not a husband she can easily divorce, it was 20th Century Fox America, which she needed to survive given that they were her only route to attaining her aspirations. The tug of war was inevitably imbalanced, with Norma Baker and the divine feminine on one side and Fox America and the male gaze on the other, the end result was terminal from the very start.

A 2012 documentary titled Love, Marilyn was produced by Liz Garbus after stumbling across the writings of Marilyn across her short years. She expresses her disdain that she was constantly cast into reductive roles, she was always the sexpot, the blonde bombshell, the obnoxious bimbo or the gold digger but never the beautiful lady with a heart of gold and the wit of a sailor. She writes, “I’ll never get the right part. My looks are against me. Too specific.” (2012). However, she fails to recognize that had it not been for her working so hard to perfect her looks, mannerisms and aura, she would not have gotten any role to begin with.

After she got her first role, she took off to practicing for over 10 hours a day, cycling between dancing lessons, vocal trainings and acting classes. In her journal she mentions, “Must make much much much more more more effort” (Garbus, 2012). She studied in a book called The Thinking Body to perfect her posture, movement, vocal texture, pitch, and tone. She assiduously labored to erect this Monroe figure, which embodies the social split created by the West. Her identity was sliced into two to the extent that once she was walking down the street with a friend, completely unrecognizable, she then turns to her friend, says ‘you want me to turn into her?’, introduces a change of manner and in a split-second drags a crowd of fans and paparazzi trailing after them.

Another incident is recounted by a friend of hers, where they were dining as she excused herself to go to the lavatory. He said waiting for her to get out was like waiting for an elephant’s pregnancy to deliver. He soon checks up on her to find her looking at the mirror and upon inquiring about the reasons she replies with, “looking at her” (Garbus, 2012). For Norma, Marilyn was an alter ego, an identity effacing an authentic identity. This identity cleavage towered and haunted her the more successful she grew. A director mentions of her “The more successful she was the more unfulfilled she was.” This is because Marilyn subscribed to the male gaze, flirted with ambitions of becoming the perfect housewife and courted the desire of spending the rest of her life nurturing a pack of beautiful little baby children.

Norma, however, had other plans. Norma writes in her journal, “My God how I wanted to improve, to change to learn. I didn’t want anything else, not men, not money, not love but the ability to act.” (2012). Yet as the media capitalized over her feminine prowess, never paying homage to the ambitious woman inside of her, she grew less and less confident in her skills.

A terminal blow to her pride was when her very husband, Arthur Miller, wrote a screenplay titled The Misfits as a Valentine present for Marilyn, in which she was supposed to play the character Roslyn. Miller painted Roslyn as a sensual, empty-headed woman who is childlike and naïve in both manner and decorum. Marilyn was more than appalled to see that her husband views her as such, and divorced him shortly after. Her health began to rapidly deteriorate after this last movie she starred in, and she admitted herself to Payne Whitney Hospital of Mental Disorders. There she suffered greatly from alienation and the apathetic treatment of the staff, and was only granted release after her second husband, Joe DiMaggio, threatened the asylum to set her free. Fox had had fired her by then for underperforming and when they had rehired her for a million dollars—the money she has deservedly been fighting for so hard—she was found dead in her house a few days later.

Her self-administered overdose of drugs poses as one of the most powerful modern Greek tragedies of the time. In his book Elia Kazan: A Life, Kazan spoke of Marilyn Monroe as “A decent-hearted kid whom Hollywood brought down, legs parted” (Kazan, 1988). He continues to mention that all young actresses of that time were thought of as prey, to be overwhelmed and tipped by the male. Marilyn’s tragedy goes to show that sexual expression does not necessarily equate to sexual liberation much in the same way that Medusa’s misfortune reveals that complicity in the face of ill treatment does not absolve one of the oppression.

It might appear facetious to draw parallels between the Arab woman’s hidden faces of Eve and Marilyn Monroe’s hidden face of Norma Jean, but the cynical undertone dissolves into a morbid reality when cast under a patriarchal light. Be it under the graves of the girls honor killed or beneath the dazzling lights of Hollywood, women have been decentered, sexualized and objectified by the man. In the documentary, Marilyn mentions in her journal, ‘I’ll never get the right part. My looks are against me. Too specific,’ exposing the exclusionary reality of American media which discriminates against women’s appearance in roles which showcase dominance and power (Garbus, 2012). The decentered yet highly prominent position Norma has been always assigned doubly obscures her struggle, rendering her representational marginalization cloaked in a shadow under the glamorous and glorifying Hollywood spotlight. Her figure, therefore, becomes the object which the male gaze mobilizes to pit female competitors against one another, misleading them into holding Norma accountable for the Marilyn figure she has equally—if not doubly—been tormented by. In a world which insists that a woman’s core value rests in her looks, adhering to the conventional standards of femininity and beauty does not open doors to countless opportunities, it rather opens doors to one steep, female-philic cliff edge.

This underlines the very limited spaces granted for women who wish to ascend any ladder situated in a hierarchy of power. Despite Norma’s diligent and successful efforts to overcome her inhibitions at the advent of her career, her role remains exclusively grounded in the attractive yet unintelligent ravishing woman who loses all her charm the minute she has to engage in intellectual debate. Being denied the opportunity to roles that showcase her cognitive prowess has plagued her with an insecurity which has accompanied to the very last day of set. It is only natural for any woman—or human for that matter—to be haunted by the impostor syndrome when they are never seen for who they are in essence yet continue to be applauded for so much of what they are not.

Another salient factor which contributes to Norma’s pool of insecurity is her harsh childhood environment, plagued with a single mother who was transferred to an asylum leaving her circulating from one foster home to another to end up married at 16 to James Dougherty. It is stipulated that her stuttering as a child is due to a traumatic sexual harassment episode, an experience she had to suppresses while sleeping her way up to the top. It is quite interesting to investigate the psychology at work where a woman objectified so early on can result in her own self-dehumanization as she treads in life knowing her only route to success is through sexualizing her bodily as well as its nontangible assets. One indispensable piece of evidence is her posing for nude photos in 1949, which were later posted in 1953 sparking controversy about her bold and daring act. She dismissed those allegations with two justifications, the first being that she was broke and in need of the money; the second being that her body is her own and she has the authority to do with it as she please. Yet could Norma here be in denial of the self-objectification she was redirecting towards the inner child which learned that she could only be desired when posing in provocative position devoid of any sexual authority? The ways in which her body has been capitalized over asserts time and time again that her body was public property. In fact, a couple of years down the line, the launcher of playboy used her nude pictures to launch the magazine which later reaped millions in profit, all the while failing to credit her and without assigning her her fair share of the revenue for the photos she got paid $50 for their taking (Garbus, 2012). The vicious cycle at play here clearly showcases the dynamics of capitalization over women’s bodies. Where a woman’s desire to feel important is exploited to create in other women insecurities which existed in the primary woman, with the middle-man, usually a director, a photographer, an executive director, or any man in a position of power, as the instigator of this self-perpetuating cycle of fueling women’s feelings of scarcity and lack. It is of no wonder, therefore, why Norma would consider herself to have ‘cooperated with her oppressors’ given the gaslighting she received in ample amount, the merit she was brutally denied and the recognition which has been repeatedly withdrawn from her.

Though much of the female has been exploited and mishandled with Marilyn Monroe, feminine power cannot be denied, dispelled or diluted. Failing to pay homage to the feminine divine inevitably creates an imbalance at the hands of which both men and women suffer. According to the Indian-American author Deepak Chopra, the divine feminine houses values human beings are in dire need of. He continues to stress that the feminine, comprising of abundance, love, beauty, wisdom, connection, nature, transformation, homemaking and healing, is present and must be acknowledged and nurtured in both biological sexes. When these values decline in the psyche, an imbalance ensues where masculine indulgence can bring about a harrowing destruction gone without check (Chopra, 2021). Chopra stresses that it is an individual responsibility to turn to these feminine values to rectify an inner imbalance.

Yet the emerging question here is: how does one come into contact with the therapeutic divine feminine qualities? Helene Cixous pertinently tackles this question in her text ‘The Laugh of Medusa’ where she positions the woman at the center and invites her to write herself, her femininity, her sensuous experience in an unfiltered light. She believes that the feminine divine will pour itself out into the safe space of the paper to bring about a radical enlightenment wholesome to all sexes.

Bibliography

Amireh, A., 2000. Framing Nawal El Saadawi: Arab Feminism in a Transnational World. Univeristy of Chicago Press.

Bevan, R., 2019. This Performance Reclaims The Myth Of Medusa After #MeToo.

Chopra, D., 2021. Why We Need The Feminine Divine.

Cixous, H., 1976. The Laugh of Medusa.

Freidan, B., 1963. The Feminine Mystique. s.l.:W.W. Norton & Company.

Kazan, E., 1988. Elia Kazan: A Life. s.l.:Knopf.

Love, Marilyn. 2012. [Film] Directed by Liz Garbus. s.l.: s.n.

Saadawi, N. E., 1977. The Hidden Face of Eve. s.l.:s.n.

Woolf, V., 1929. A Room of One’s Own. In: s.l.:s.n.

![]()